Legacy and the Public Realm: Dreaming with Frank Gehry

- Speaker

- Frank Gehry

- Media Type

- Text

- Image

- Item Type

- Speeches

- Description

- October 3, 2013 Legacy and the Public Realm: Dreaming With Frank Gehry

- Date of Publication

- 3 Oct 2013

- Date Of Event

- October 2013

- Language of Item

- English

- Copyright Statement

- The speeches are free of charge but please note that the Empire Club of Canada retains copyright. Neither the speeches themselves nor any part of their content may be used for any purpose other than personal interest or research without the explicit permission of the Empire Club of Canada.

Views and Opinions Expressed Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the speakers or panelists are those of the speakers or panelists and do not necessarily reflect or represent the official views and opinions, policy or position held by The Empire Club of Canada. - Contact

- Empire Club of CanadaEmail:info@empireclub.org

Website:

Agency street/mail address:Fairmont Royal York Hotel

100 Front Street West, Floor H

Toronto, ON, M5J 1E3

- Full Text

October 3, 2013

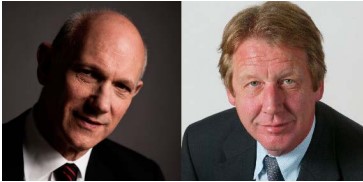

David Mirvish In Conversation with Christopher Hume Legacy and the Public Realm: Dreaming with Frank Gehry

Chairman: Noble Chummar, President, The Empire Club of Canada

Head Table Guests

Dr. Gordon McIvor, Executive Director, National Executive Forum on Public Property, and Director, The Empire Club of Canada;

Rev. Chris Miller, Retired Minister, United Church of Canada, Chaplain, Context TV;

Verity Sylvester, Director, CV Management Inc., and Past President, The Empire Club of Canada;

Ian Troop, CEO, Toronto 2015 Pan American/Parapan American Games Organizing Committee;

Patrick J. Monohan, Deputy Attorney General of Ontario, and Ministry of the Attorney General;

Jack Robinson, CEO, CN Tower, and Chair, Toronto Entertainment District BIA; and

Peter Kofman, President, Projectcore Inc., working with David Mirvish in the Capacity as Project Lead for Development.

Introduction by Noble Chummar

It now gives me great pleasure to introduce our moderator, who has been with us before, and will ensure that this will be quite an interesting talk. Mr. Christopher Hume is no stranger to the City of Toronto. He was born in England, came to Toronto as a child, and has spent his career writing on issues of architecture and urban affairs. Christopher is someone who has received countless awards and recognition for his journalism and writing. Most notably, he was awarded the very prestigious National Newspaper Award. Mr. Hume understands the City of Toronto. He is an expert in architecture and the history behind our city’s buildings, and the many stories behind those buildings. Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Chris Hume.

And now for our guest speaker. Great children are the product of even greater parents. David Mirvish is someone who was fortunate to be raised by two great and patriotic Canadian parents. First of all, on behalf of everyone, Mr. Mirvish, please accept our most sincere condolences on the recent loss of your mother, Anne. The Empire Club has rarely had the opportunity for father and son speakers to have a place in our iconic red books. I’m not sure of too many— Pierre Trudeau and his son, Justin, recently and the Queen Mother and her son-in-law, Prince Phillip. In 1981 and in 1989 David Mirvish’s father, Honest Ed Mirvish, addressed the club. This was the kind of guy he was. One of the speeches was titled, “How I Became an Overnight Success Story in Seventy-five Years.” David Mirvish has the genetics of a true patriot Canadian entrepreneur. Mr. Mirvish is someone that thinks big, real big. The Mirvish family has been a pillar of the arts and culture and entertainment in our great city for several decades.

More recently, David Mirvish teamed up with the world-famous architect Frank Gehry. They’ve proposed a monumental transformation of our city, with two 80-storey residential towers described by Mr. Mirvish as sculptures that people can live in. What would Toronto be without our CN Tower? I am sure there were many people opposed to that structure when it was built almost 40 years ago. But it’s a building that defines our city. It’s the one thing you look for when you’re flying back home. You look out the window and know that you have arrived back home. Our buildings define our cultural identity. They boldly and quietly influence the enjoyment of urban life. They tell a story of the kind of people we are. The people of Toronto are creative, diverse, imaginative and intelligent. Our buildings leave a cultural legacy to generations of citizens and visitors who come to live, work and play in our growing metropolis. David Mirvish is President of Mirvish Enterprises, which include Mirvish Productions, Ticket King, the Mirvish theatres, which are the Royal Alex, the Princess of Wales, the Ed Mirvish Theatre and the Panasonic Theatre, and the iconic retail emporium, Honest Ed’s, named after his father, which is celebrating its sixty-fifth year. Mr. Mirvish is a member of the Order of Canada and we join his family in celebrating 50 years of presenting and producing live theatre, both locally and internationally. Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Mr. David Mirvish.

Christopher Hume

I’m here just to ask the questions. I know you’re here to listen to the answers. The fact that this event is sold out and that there was a demand for a number of additional tickets is an indication that this is a very unusual, even unique, project. I think that it’s important to keep in mind before we start that David is not a developer in the traditional sense of the word. This is not just another condo, which is why I’m so interested in this project. I’ve been writing about condos for more years than I care to remember, but I’ve never seen a project like this. It hasn’t been built yet, of course, but I do believe quite sincerely that it’s something that we as a city have to embrace and take a serious look at. We’re going to talk about that more in a while. David wants to start with some images of stuff that Frank Gehry has designed and built around the world. And of course, he’s worked here in Toronto too. You all know about the Art Gallery of Ontario, which he renovated and transformed into the building it is now. But I think it’s also important to keep in mind that this would be Frank Gehry’s first and only freestanding structure here in Toronto. And don’t forget that Frank Gehry was born and raised in this city. I think this makes the project unique, and I think it makes it important. I think it makes it more than a condo, and I hope that over the course of the next half hour you’ll be able to find out what I’m talking about and agree with me. I know not everybody does, unfortunately.

First of all, let’s get some pictures up here. David, why don’t you take us through this?

David Mirvish

Okay. Well, we started out with very different images from this. We had deep discussions with the city planners, who eventually said, “Would we evoke warehouse?” We have warehouse buildings in this neighbourhood and we’ll talk about that later. But after five or six attempts, I turned to Frank and said, “Let’s give up. We can’t do it.” And he said, “No, no. I’m into this. I want to take one more shot at it.” So he came up with this building. When you see this building in close-up shots you’ll see how he did evoke warehouse.

These are pictures of other projects as early as 1995. This building in Prague, which some people refer to as “Fred and Ginger,” surprised people but it’s a residential building fitting in with older buildings, and it is meant to do that, a sort of made-in-Toronto solution. This is the building that I think drew everyone’s attention to Frank in some ways—Bilbao, Spain. Bilbao is a city that reminded me, I think, of Hamilton, and this transformed the city.

Christopher Hume

Bilbao is the Hamilton of Spain. It has a population of half a million, is a shipbuilding city, a steel town on the Atlantic coast. It had lost something like 125,000 jobs over the course of two or three years and had hit rock bottom. The interesting thing about Bilbao is that the various levels of government there, unlike the various levels of government here, decided that they would renew themselves, re-invent themselves, through the power of architecture. This is the most celebrated example of what they did. They also got Norman Foster to design their subway stations. Bilbao went from being a city that nobody had ever heard of to one of the 20 most visited cities in Europe. The effect of the building was so enormous that it was called the “Bilbao Effect.” Ever since, cities everywhere have been trying to copy this example. Nobody has managed to match it yet, but it’s still something that people and cities are trying to do. I think that this is something that we have to keep in mind when we look at a project like the King Street one. This is a lesser known Gehry project in Germany. This is the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. This was actually designed before Bilbao, but built afterwards. You can see that these are the buildings that made Frank Gehry the superstar architect of his generation. And I would just add here that Frank Gehry is 84 years old, something else to keep in mind. This is our own AGO. This is the project where Frank Gehry reminded us that it’s not always about spectacle, but about the simple things—how you get in, how you move around, and create a space where you can have an experience of art. His intervention has had an enormous effect on the Art Gallery of Ontario. This is the Serpentine Gallery Pavillion in London.

David Mirvish

This speaks about Frank’s love of materials and of wood, something that is of interest to both him and me.

Christopher Hume

Las Vegas, Nevada. This is not the kind of place where you expect to find serious architecture, but this is one of the few non-kitsch pieces in that city. I don’t know this project.

David Mirvish

This is for Michael Tilson Thomas. It’s a music centre, but you can hear the concerts inside, or outside on the lawn. This is a picture of the evening outside on the lawn. It’s an extraordinary music hall that can be altered to take any size of orchestra or any small group. It’s where people go from the Julliard as a transition between it and the great orchestras of the world.

Christopher Hume

This is the most recent high-rise condo in New York. It is already a landmark, visible from the High Line, which seems to have been built as a place to view this very building. Like so many Gehry buildings, it changes as the light changes. There’s nobody who is better able to incorporate a sense of motion and movement into his architecture than Frank Gehry. Again, we would be the beneficiaries of a lifetime of experience. And the fact that this is his hometown, the fact that this is a unique opportunity, is something that I think is very exciting. So here are more views of the same tower, which I think won an award last year for the best new skyscraper in America. Ours would be much better, much more interesting.

David Mirvish

Here’s a very unique site in Hong Kong on a hillside—a series of, I think, 12 storeys of apartments, each one full floor. It is a sold-out residential building. People wanted to be there.

Christopher Hume

By Hong Kong standards, it is not very tall at all.

David Mirvish

No, but quite spacious. They’re 6,500 square-foot apartments. They sold for $65 million. We don’t have that same market. This is, I think, the most exciting part because this is in Bois de Boulogne in Paris. This is the Foundation for Creation. It’s been nicknamed “the Cloud.” And Jean Nouvel said, “The history of Paris is in its buildings. And once this building is open, it will become a part of us and make Paris better known than even today. The building opens next year with a whole year of celebrations and it’s essentially a museum for the Louis Vuitton Foundation. It will show contemporary art, but it will also show designs and products. It was meant to make Paris the centre of creative activity, focus on creation around the world, but also focus on French culture.

Christopher Hume

I think that’s it for the slides. Oh no, I’ve got one more here.

David Mirvish

Abu Dhabi is yet to come, and then I think that is it.

Christopher Hume

Well, let’s just hang on here for a second, because I think that before we get into the actual project, we should set the stage. It begins in 1963, when your father, Honest Ed, bought the Royal Alex on King Street.

David Mirvish

Yes, the Royal Alex; we’ve been there now for 50 years. We’ve put on 500 or so plays. My real business is live theatre and I have four theatres in the city now. My father, when he bought it, really knew very little about theatre. My mother went but he didn’t really have the time. He went to Honest Ed’s. He had been to a show with me the year before, but he renovated it because he thought it was a beautiful building. What he didn’t realize was the greater sweep of history that was involved in the neighbourhood. In the 1870s, the corner of King Street and Simcoe was once what we today call the public realm, the place where people went in and out of buildings. The northwest corner was education; there was Upper Canada College. The southwest was legislation; it was the provincial legislature. The southeast corner was education and legislation.

Christopher Hume

Damnation.

David Mirvish

No, the one before damnation. Salvation, salvation. St. Andrew’s Church is still there, and it’s the only thing that actually has survived. And then to the northeast was damnation. That’s where the tavern was, but all those places were about people going in and out. This is the 1870s. And then in 1907, the Royal Alex was built, which was also part of the public realm, and the Lexington Hotel where TIFF is today. In 1912, the railroads were built on the whole south side of King Street in front of the Royal Alex and in front of TIFF, where Metro Hall is today.

Christopher Hume

And Roy Thomson Hall.

David Mirvish

And Roy Thomson Hall. They stored trains there. These were the stockyards. This was the end of the track. And they began to build all of these warehouse buildings in the neighbourhood. So from 1912 to 1963, this was taken away from the public and made into these warehouse buildings, where people went in at the beginning of the day and out at the end of the day, where it wasn’t inviting because it was raised up and you had to go up steps or go downstairs. And there were little windows to let you see some daylight if you worked in the basement. My father didn’t know better. He bought a theatre. It was supposed to be turned into a parking lot.

Christopher Hume

Torn down to make way for a parking lot.

David Mirvish

The city had moved on and was moving to the east. We had built the O’Keefe Centre, and that was to take over for the theatres. My father was a shopkeeper. He didn’t know that you’re supposed to keep your theatre closed if you don’t have a really great show. He thought it was a habit to go to the theatre. So he was open 50 weeks out of 52 a year. And at one point, he was desperate. The show was so bad. It was called “Return to the Mountain.” He said, “Look, I’m not even going to charge you. There’s a bucket on the way out. Throw what you want in, okay?” And so from 1963 to now, we grew. When the theatre was by itself, 10 to 12 thousand people went in the wrong direction every week. The result of that was he wanted to make it easy for people and attract them so he bought the warehouse next door. He didn’t know how to cook, so he went to friends like Harry Barbarian. He asked, “What do I make for these people?” And Harry said, “Make them roast beef. You can work all day at it and you just have to slice it when they come in.” He bought all the peas on a farm and put that with it and he was all set. At its peak he served 6,000 roast beef dinners on Saturday night, which was, if you want to work it out, 75 head of cattle. So he changed the direction of people. Restaurants began to open around him. People began to build around him. We built Metro Hall. There was a hotel down the street. And then people began to build condos around him. And then TIFF was built, our most recent neighbour. And so what had once been an industrial area turned into a residential neighbourhood. A lot of credit should go to Barbara Hall, in 2002, who said, “These don’t have to be light industrial buildings anymore.” When we had the restaurants, the city came to us and said, “Tear down the top three floors over them. You can’t have workers above what might set a fire in a wooden building.” So he emptied those buildings and kept them empty until 2002. In the last 10 years we converted them and we now have them as places where there are companies like my own, which deals with tickets and deals with theatre, and companies that deal with ideas about water and all sorts of interesting activities providing jobs. What he really did is that from 1963 to 2013 he brought the area back into the public realm.

So today, the discussion is, “Do we keep the remnants of the public realm?” This is the crux of my discussion with City Planning, that is saying, “These warehouse buildings are more important than Frank Gehry.” And I’m saying, “No, what’s important is we’ve now got all these people coming into the neighbourhood and there’s traffic on the sidewalk.” Those sidewalks are narrow because warehouses don’t want them. They build right to the street line. Let’s pull back from the street line. Let’s pull back from the corners. Let people have room to move. We’re going to keep the Royal Alexandra Theatre. We have TIFF on the other side. We want John Street to be a cultural corridor and to link the Art Gallery of Ontario to the Aquarium and have activity on John Street. You can’t have people coming to the Princess of Wales on John Street and parking going through that building over to John.

Christopher Hume

So David, let’s show some pictures so people can see exactly what you’re talking about. And let me just say ahead of time that the model of development in Toronto has been, as I’m sure you know, the idea of the tower on the podium. It wasn’t always that way, but it has been for the last 15, 20 years. And the idea, the principle here, is that you activate that street level. You have shops, stores, restaurants, so on and so forth, so that you maintain the street level. You maintain that street activity, and you put towers on top of that podium, and the towers that we prefer now in Toronto tend to be tall, thin towers. So height is a big part of it. We’re going to talk about this in a few minutes, but the city has raised a number of objections to this project and none of them are valid, I would argue. David, of course, is much too polite to say that but I’m not. So what we’re looking at here is the ground level of the project. And David, maybe you can go into a bit more detail on what we’re seeing here.

David Mirvish

Yes. You have to understand how Frank Gehry works. We start out with the first images that we showed the public a year ago when Frank was 83; he is now 84. And I’d like to point this out because all he wants is to come home. He wants to do a great building in Canada. But he also doesn’t want to spin his wheels, because he has only so much time to do so many buildings. He has extraordinary buildings going on everywhere in the world at the moment. But when I said, “Let’s give up on evoking warehouse,” he said, “No, no. I’m going to use wooden beams and glass and bring it to the front of the building, but I’m going to bring the building line back.” So you’re looking at the north- east corner of John and King on the left-hand side here, and the entrance into the stores. There will be about six floors of activity in the lower parts of these buildings that are inviting to the public, where we want the public to come and go. But unlike the Princess of Wales, which brings them all in at one time of the day and crowds everything at once, that same traffic will now get spread out through the day and be absorbed in another way. And then he’s taken these romantic—I think romantic because I think a curve is always romantic—shapes and protected people from the street with canopies that I think evoke 100 years earlier. Paris and Guimard are the references for me; the sense of the curvaceousness that art nouveau was able to express at that moment, that made that city so distinguished.

Christopher Hume

Let’s just talk and explain a little bit more. In the first version, the city felt that these old warehouses were gone and that they were a heritage element in the city worth saving. Normally, of course, one would agree with that. And so, their request was that Frank Gehry try to reflect in his architecture this industrial heritage. It’s hard to see on this slide here, but there are a number of thick, heavy wooden beams that are meant to evoke this history, this particular element of the history of King Street. The parts that you see coming down, the Guimard elements that David’s talking about, are glass. There is essentially a rectangular building behind them, and these glass elements come down. They’re sort of not fully opaque, not entirely transparent, but kind of a milky sort of glass that would let in light, but as David says, they would provide sort of a protective element. Should we go to the next slide?

David Mirvish

Yes, I think that would be helpful. Now you can see a little closer the wooden beams on the various floors. This is one of the corners. It’s a mix of stores. It’s a mix of university— OCAD University is going to be a part of this—and a mix of art gallery. I’ve spent 50 years of my life collecting visual art, and will put the core of that collection into 60,000 square feet of it. That will have to be backed up with about 100,000 square feet of warehouse space out of the city in order to feed it. And people don’t quite understand what those interrelations mean. I spent some time the other day with some of the senior teachers at OCAD, and we were talking, because they’re looking at putting curatorial studies and fine art history into this location. As they began to look at my collection, they could see that they had a tool they could work with, which would give them some differentiation from what other universities were capable of doing, because of the access to certain material. I look forward to that. I went recently to the Peggy Guggenheim museum in Venice and spoke with Philip Rylands, who has run that institution now for 33 years. He said, “We have 1,500 interns that apply for 30 positions, and they come for three months to live here.” They all have BAs. They’re working on MAs or PhDs, and they go off later. They’re all in philosophy, or fine art history, or architecture. And then they go off and they talk about our museum. Sam Mendes is coming to visit me next week. Sam did “American Beauty,” the film. He was an intern and much of the imagery there comes from the Magritte in that collection. So a lot of inspiration, a lot of dialogue. It’s a way of connecting Toronto to the University of Tokyo. It’s a way of connecting us to a university in Prague. It’s a way of having a dialogue between cities. So you have to understand that the nature of the jobs are complex as to what’s going to go on this building. At the same time, I’d love it if Rem Koolhaas would put United Nude in. He makes computer shoes for ladies. This is such an extraordinary and unique store. And why wouldn’t we have an extraordinary little cheese store? And why wouldn’t we have a great bookstore? Why wouldn’t we have the elements of what make this a community and a place to live. Most of the cities in Canada are symbolized by our bank towers. They dominate our downtowns. Maybe where we live is as important. Maybe where we live should rise to the same height and have the same presence. On one side, we have a lot of wonderful institutions. They’ve been very successful at what they do. If their employees wanted to live near them and be able to walk to work in 10 minutes, wouldn’t that be a wonderful juxtaposition, and wouldn’t it be wonderful to say to the world that living and how we live and where we play and what we do is as important as how we make our livings.

Christopher Hume

We are going to talk about the towers in a second. But the podium, the six-, seven-storey podium is where the public part of this project is. Think about the typical form that development takes in Toronto. You have a dry cleaner, a sushi, and maybe a Tim Hortons at ground level, and the people who live and build these condos are happy to have these tenants in their building. The point here is that you have TIFF on one side. You have the Royal Alex. You have the addition of OCAD University, an art gallery, these teaching facilities, and the idea of the John Street corridor, which has been around for maybe three or four years and hasn’t really gone anywhere yet but still could. You create a kind of critical mass here, and of course then there’s the building itself. And the building itself is sculpture. Frank Gehry has always been very up front about the fact that he sees himself at least as much as a sculptor as he does an architect. This would be unique in Toronto, and, with the John Street corridor, would tie the whole thing together all the way up from Dundas, with the AGO, right down to the lakefront. Here are more pictures of the podium. You can see the wooden beams that David has talked about.

David Mirvish

There also is an echo of the Italian Galleria in the Art Gallery of Ontario with this. So it links the neighbourhood. It actually speaks to that. Frank lived on Beverley Street. His grandmother was there. So he wants to use clay and brick also in the buildings and in the tower. We’re exploring different materials. Where we’ll end, we’re not sure. This is how Frank makes a drawing. He builds models. He told me there would be 75 models before we’re done. We’re somewhere around model 45. The volumes and shapes are there and this is part of the great adventure. It doesn’t fit into the normal box. It doesn’t fit into the way people usually work. You have to give enough room for creativity. I’m used to buying art that hasn’t quite been finished or isn’t quite dry yet. So this is just another piece of that. That’s the street, Ed Mirvish Way, which is sometimes called Duncan Street.

Christopher Hume

I think it’s interesting to talk about Frank Gehry for a second, because he left the city when he was 17 or 18 in the late 1940s. But it’s always been very important to him to be Canadian. In fact, he is a dual citizen. If you look at the textbooks, he is always described as a Canadian-American architect. If you go to his office, you’ll see that his walls are covered in hockey paraphernalia. He’s a big hockey fan. So the Canadian element, the Canadianness of Frank Gehry, is something that it’s easy to forget, because everybody thinks of him as being American. But for him, this is an important thing. It would be the culmination of a career that has lasted a long time. I know that you met Frank Gehry before he was famous.

David Mirvish

I had an art gallery in Toronto from 1963 to 1978, and in 1971 I showed around a Californian artist named Ron Davis. He had just had his studio and house built by a younger architect named Frank Gehry. I did a dinner for Ron and they both came. That was the first time I met Frank. I stayed in touch over the years, off and on. But Frank really didn’t gain attention until about 1976 with his own house, and then real worldwide attention with Bilbao. People sometimes don’t quite understand, because I’ve gone for the grand gesture. Toronto matters as a city and we should stand up and we should be seen and be willing to take a place amongst other great cities. Frank, in the intimacy of what he does, is very responsive. I had some qualms about the first drawings of the art gallery but I didn’t even have to announce them. He could get it from one or two sentences and my body language and came back with a much more responsive program that fitted what I wanted. He’s very much textural. He fits into contexts. He’s very much aware of where these buildings are going and what their relationship is to the rest of the buildings around him. His models are not built in isolation. They’re built with whole city blocks built out around them so that he can see where these are going to fit in. We’ve tried to fit within the new city guidelines about spacing. The old city guidelines were 18 metres between towers. The new ones are 25. We’re very close to fitting exactly those twenty-five. So he’s very thoughtful about what the needs of a community are. He doesn’t want to build a building that isn’t going to succeed. He wants to build a building that we won’t know how good it is the day he builds it. We only know now with hindsight how great the TD Bank building is.

Christopher Hume

Frank Gehry’s sensitivity to context is an important point. If you go, for example, to the AGO, and you go to the Gallery Italia, it is a viewing stand from which you can see the city spread out to the north in front of you. I remember talking to him when the gallery was opening, and he was very proud of that fact. It wasn’t a coincidence. It didn’t just happen. Even a building like the Guggenheim in Bilbao makes all kinds of very urbanistic gestures. I think that we tend to get sort of carried away with the spectacle of his architecture, but he’s actually very sensitive to context. As I say, the Guggenheim connects the river to the city. It even opens up to allow transit to move through. And that, I think, he takes great delight in. One of the reasons I think this project is so important is because it’s about the public realm. It’s not just another developer trying to make as much money as possible selling as many condos as possible. That’s not what this is about, although it’s the condos that make it economically possible.

Christopher Hume

Another view from street level. This is looking west, I think.

David Mirvish

I think it’s really important that we have retailing in this neighbourhood. We have three very high-end hotels—the Trump, the Shangri-la and the Ritz-Carlton. And yet there’s no shopping that really holds people in the neighbourhood. They all have to go to Yonge and Bloor or to Yorkville. Great cities usually have two or three areas where these activities take place, and I think that there’s a role on the ground level and on the second floor that’s important, where we can have anchor tenants in the corners.

Christopher Hume

And, in addition to that, it’s metres from a subway station.

David Mirvish

So close.

Christopher Hume

And then there’s the King streetcar, soon to be replaced, of course, by a brand new twenty-first century LRT, and at some point in the future, closed off to cars. So they consider, or so we hope.

David Mirvish

Don’t hold your breath, but we’re working on it.

Christopher Hume

It will happen. This is the building that anticipates Toronto’s future. And when it finally arrives it will be sitting there, ready, willing and able. Let’s look at the towers now. David, why don’t you start this?

David Mirvish

Well, Frank was faced with a conundrum. Usually you have a base and a tower, and he wanted to unite them. In a way, he’s created three vases—one iron tower, a glass tower, and a clay tower. But they’re really like three flowers growing out of a vase. Now I’m being metaphorical and I hope you don’t expect me to water them. This material he has used before on the west side of Manhattan in a building he did there. It worked very beautifully and he thought he could make it even more interesting. He can use a milkier glass that you’ll be able to see through at night and it will be opaque in the daytime. So we’re playing with materials. As I say, we may not be able to afford this much architecture. But part of the hype and part of the density has to do with being able to pay for architecture and also to be able to pay for an art museum. Most people can never do an art museum because how do you sustain it? And we’d like to not have to charge the public. We would maybe have to charge for special exhibitions, but we’d like to have it funded to the level that we allow the public in. And that’s where the rents of the commercial space play a role. So all of it comes together in different elements.

Christopher Hume

We only have a few minutes left. Why don’t you tell us exactly where the project is in the approval process?

David Mirvish

Well, the latest information that I have on it is we’ve been in dialogue a full year now. There is a made-in- Toronto solution that we are often confronted with. The made-in-Toronto solution is to fit in with what exists. Don’t put your head up too high. Don’t stick out. If we would like to do one tower next to the Royal Alex and maybe one tower between two of the warehouse buildings, and therefore eliminate the public realm from the corners, and not make the sidewalks wider, I suspect we could get permission. I think that’s where we’re at.

Christopher Hume

So when will you be at the Ontario Municipal Board?

David Mirvish

In January.

Christopher Hume

In January. So that’s when we’ll find out what happens. I think, David, we’ve run out of time. Thank you very much.

David Mirvish

Thank you. A pleasure.

The appreciation of the meeting was expressed by Dr. Gordon McIvor, Executive Director, National Executive Forum on Public Property, and Director, The Empire Club of Canada.