A Trip Through South America

- Publication

- The Empire Club of Canada Addresses (Toronto, Canada), 9 Feb 1922, p. 30-49

- Speaker

- Walker, Sir Edmund, Speaker

- Media Type

- Text

- Item Type

- Speeches

- Description

- The speaker's "grand tour" of South America. Differences between North and South America. Misconceptions about the weather in South America. Reasons for climactic differences on the two continents. The misconception that South America is a continent of black people, and evidence to the contrary. The peoples of South America. Our greatest error in thinking that in material civilization South America is inferior to North America, and evidence to the contrary. The great cities of South America. Population of South America. Transportation and developments yet to be made. Geography of South America. A description of the speaker's travels in South America and his impressions of the continent and countries therein. A detailed description of Rio, including architecture and life lived by the sea. Other places described include Buenos Ayres, Sao Paulo, Montevideo in Uruguay, and Brazil. The English company Dumont Epasinade, and the German company Smease. Coffee production. Business and industry. A brief mention of Chile and Peru. Some general statements about South America. Capital from England for railways and other development. Manufactured goods going to South America mostly German. The potential in South America for Canadian goods. How British and foreign trade I built. Differences between how North America and South America were settled. The need to understand the people of South America. Differences in manner.

- Date of Original

- 9 Feb 1922

- Subject(s)

- Language of Item

- English

- Geographic Coverage

-

-

Ontario, Canada

Latitude: 43.70011 Longitude: -79.4163

-

- Copyright Statement

- The speeches are free of charge but please note that the Empire Club of Canada retains copyright. Neither the speeches themselves nor any part of their content may be used for any purpose other than personal interest or research without the explicit permission of the Empire Club of Canada.

Views and Opinions Expressed Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the speakers or panelists are those of the speakers or panelists and do not necessarily reflect or represent the official views and opinions, policy or position held by The Empire Club of Canada. - Contact

- Empire Club of CanadaEmail:info@empireclub.org

Website:

Agency street/mail address:Fairmont Royal York Hotel

100 Front Street West, Floor H

Toronto, ON, M5J 1E3

- Full Text

- A TRIP THROUGH SOUTH AMERICA

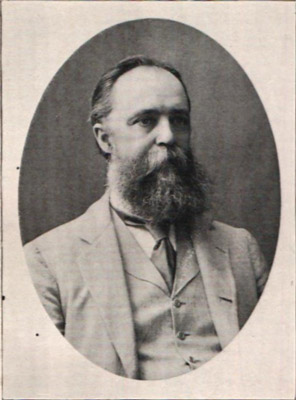

AN ADDRESS BY SIR EDMUND WALKER, D.C.L., LL.D., C.V.O., PRESIDENT OF THE CANADIAN BANK OF COMMERCE.

Before the Empire Club of Canada, Toronto,

February 9, 1922.THE PRESIDENT, Sir William Hearst, introduced Sir Edmund who was received with loud applause.

SIR EDMUND WALKERSir William, and Gentlemen,--I had the pleasure of addressing an audience in New York in the middle of the war, and in telling them of the various types of people in Canada, and in trying to account for the difference of point of view between the two countries. I told some Highland stories. One was about Greenfield MacDonald of Glengarry, who, being in Ottawa when the Marquis of Lorne was GovernorGeneral, received an invitation to attend a state dinner, which he immediately declined; but feeling that an explanation was necessary, he wrote in the corner-"P. S.When did a MacDonald sup with a Campbell?" (Laughter) I told my story, and at the end of the address a great big fellow came forward and said to me, "I was very much amused to hear you tell that story about Greenfield MacDonald; I am from Glengarry myself, and it is just the sort of thing that he would say." I was very

-----------------------------------------------------------

Sir Edmund Walker is president of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, chairman of the Board of Governors of the University of Toronto, founder of the Champlain Society, fellow of the Royal Colonial Society and of the Royal Society of Canada, and Consul-General for Japan. He is the author of many papers and reports on banking and an art connoisseur of distinction.

-----------------------------------------------------------

gratefully relieved that that was the turn his statement made, because I realized the great danger of speaking to a public audience and talking about things that you don't really know much about, for fear that at a later time somebody should come forward and say, "You were quite wrong when you said this, and said that."

I was only in South America on what they call "the grand tour," and therefore was there for a very short time, ten or twelve weeks. The only service I can perform today is to try and point out the differences between North and South America, on the presumption that you have been to some extent in the state of error that I was in myself when I went to South America.

To begin with, we are very apt to think that South America, is a warmer part of the world than North America, whereas the very reverse is the case. We are partly under the misconception, I suppose, because the equator runs through part of Brazil and through Venezuela and the Guineas, and therefore there is a great black belt there, and we are apt to think for that reason that it is warmer. As a matter of fact, at the same point from the equator South America, is always colder than North America, and naturally so when we reflect that in North America the Gulf Stream runs by our shore on the Atlantic side, and the Japan current runs down our shore on the Pacific side, while in South America on the Pacific side the Humboldt current, a cold current from the Antarctic, comes all the way up to the Isthmus of Panama, affecting the climate of that country. I may say that at the same distance from the equator we can illustrate that by Buenos Ayres, the farthest point south that we happened to visit. It is the same distance from the equator as Nashville, Tennessee, but, as you will see from some of my remarks, Nashville is in the black man's country, a subtropical country, whereas Buenos Ayres is not sub-tropical, but very much like this part of Canada. We are apt, also, to think of South America, or at least I used to, as a black man's country. Our steamer being late in leaving New York I touched at Bahia. We touched first at Rio, and I reached the city which is in the twenty-third parallel south from the equator while Washington is thirty-eighth or thirty-ninth; yet Rio has very few black people, and Washington has, of course, a great many. I do not mean that Rio has few black people as compared with us, but it is not in any sense a black country.

Again, the southern parts of Brazil, and all the country of Uruguay and the Argentine, is a white man's country, and in the main a country settled by white people during the past two or three generations from Europe, not even to any great degree a Spanish country.

On the Pacific side there are people of Indian descent, pure Indian blood as far as that is possible. In the central part of Brazil there are many wild, untamed bands of Indians. But still we come to a country which is only black in the tropical or equatorial part, and which is a white country, andexcept to the extent of the descendents from the Portuguese and some Spaniards-is a comparatively recently settled white country, with a freedom from black or inferior races to a greater degree than we are apt to think.

We are apt, also, to think that in material civilization--at least one was until we heard so recently--that South America is inferior to North America. That is one of the greatest errors we are in the habit of making. The great cities of South America are quite in advance of our northern cities, whether in buildings, streets, or other appointments, and there is no city in North America to compete with Buenos Ayres except New York. Chicago certainly does not. There are very few cities to compare with Rio. I am not, of course, discussing the wisdom, or economics, or anything of that kind; I am merely stating facts as one sees them. In all cities the public parks, squares, special avenues, which are generally called the avanada, and bearing no other name, in municipal theatres, opera houses, stately private residences, hotels, tramways, the buildings are finer than ours, and upon them a great deal more money has been spent than we, as a rule, are willing to spend. The country parts are far behind North America; and of course you will see that I am not speaking of a scheme which we should imitate, but I am merely stating conditions as one finds them.

The whole population of South America is only 40,000,000--only five to the square mile as compared with thirteen in North America, and 104 in Europe, and I should think that a great deal more of South America is suitable for cultivation than North America. Then again, they only have 30,000 miles of railway as against 38,000 or thereabouts in Canada, and although about one-third is in Brazil, a little more than one-third in Argentina, which, however, has two states that are quite thickly settled with railways, and a little less than one-third over all the rest of South America. So that there is less, by nearly 25 percent, in all South America than in Canada. That gives you an idea of what development on the line of transportation has yet to be made.

Now, if we think for a moment that North America is primarily the result of the Pacific Cordilleras, the Pacific Mountains on one side and the Alleghanies on the other, and a great basin in between through which the sea poured not so very long ago, in geological times, and that our fertility comes from that great country of sea-drainage and of glacial drift; if we realize that, and think of South America in the same way, we will discover that there the most ancient part is Guiana and Venezuela where the mountains are older, they have been longer above the sea than in any other part. Trinidad is a broken-off piece. Then the mountains, from a little south of the Amazon clear away to Patagonia on the Atlantic side are extremely ancient mountains, the age of our own Alleghanies and ancient Laurentian rocks--here smooth externally because they have the extremes of heat and cold, and not ragged as they are with us-and they are covered with beautiful tropical foliage on the ancient mountain system. On the opposite side is the system very much the same as we have.

The sea came in from the Atlantic in that area between this one group of the Pacific mountains and those two groups of mountains on the Atlantic, and as a consequence, in its final decision it has left an area with 3,700,000 square miles of land, almost every acre of which is of unusual fertility. Try and bear that in mind when you think of what the future of South America must essentially be.

Despite those mountain barriers, there are breaks on the Atlantic side which give to South America, some of the very best ports in the world. On the Pacific side, like ourselves, but worse off than ourselves, there is almost no part that is suitable or can be made suitable for navigation without a great expenditure of money.

We sailed on the 23rd of February; and, Gentlemen, in thinking about South America. one may just add six months to his date, and get an idea of what the weather would be like-just about half a year different from ours. We went down direct to Rio, but there are those who think that a much cleverer trip is to go through the Isthmus of Panama and go down to the Pacific side and cross the mountains to Buenos Ayres and come up; but whether one comes one way or the other, the transit is very comfortable and very pleasant. We went by the Lampman and Holland Line, by the steamer "Oban" with a splendid officer, who was a captain in our Navy. I mention that because we people who care about the British Navy will be interested to know that there are two lines of steamers--the Lampman and Holland and Royal Mail Line which for sixty-five or seventy years have persistently sent ships from Great Britain to South America, and whether bad times have come or whatever has happened they have not been deterred from keeping up their connection with that part of the world (Applause)

We had uniformly fine weather. People talk about the heat in the tropics. There was no heat in the tropics; four or five days of nice cool weather before we went through the tropics were like an August day in Canada.

We reached Rio in sixteen days. Of course everybody asks whether Rio is as beautiful as people say. It is really like asking which is the best orchestra in the world or the best choir in the world. There is no answer. Rio is like nothing else. It is one of three or four of the most beautiful places in the world, and when you go there you will be unable to resist the idea that it is the most beautiful. We could go any day at any time and could see those most extraordinary coral peaks, and see the hills all around against an almost darkening sky; and what we noticed most was the semicircle, that was twenty or thirty miles in length, but broken here and there, where the curve went through the tunnel because of some projection of the mountain; and the extraordinary semi-circle of beautiful lamps, lighting up this perfectly wonderful city. When one reflected that all this lighting and all the engineering in connection with it was done by a Canadian company it gave one a thrill of pride, even if one did regret the fact that they had not paid a dividend for some time. (Laughter)

The Bay is about twenty miles long; it is literally called "The Bay of a Hundred Islands." You cannot look in any direction without seeing fifteen or twenty mountains and thirty or forty hills. Islands and mountains are in every direction, and Rio is built upon such flat or sloping surfaces as can be found between those mountains. Suitable and typical beyond imagination as a place to build a large city of esplanades and avenues, to develop all the frontage, which indicates the civic pride in the city and the extravagance but willingness to spend money when they have it, or when by credit they can get it; certainly not the thing which we should desire to imitate, but something that at all events makes one a little bit ashamed of our splendid plans for waterfront and parks and so on which have remained year after year developed to such a slight degree.

The city has a population of 1,200,000, and while it has many narrow streets in the old parts, the new streets are all very wide, and sumptuously so, and right through the centre of the old city is a magnificent avanado built by the city, coming out 400 feet in width, even taking out the cathedral and building the street nearly 200 feet wide, with business premises on each side, and doing so quite satisfactorily, I believe, from the point of view of economy, and enormously helping the city's traffic. I could not help but think of the effort made by the Civic Guild twenty years ago to build backward in Toronto to relieve our congestion, and the promise made by business men here that were we to be allowed to do such a thing here in Toronto, we could build two wide avenues fronting the property, and that it would cost little or nothing to do it.

The architecture of South America is always stipple. The building may be adobe or a brick building, or a solid structure as any buildings in the world, but the exterior wall is always stipple, as throughout almost all of continental Europe. Now, stipple is of course such an easy method that, like all easy methods, it runs to flamboyance; when people have a chance to express themselves they are apt to make all that is inside and that is outside of themselves in one form or another flamboyant, grandiose, and sometimes ridiculously so; but other times it is the expression of the most beautiful things in architecture, especially from the French schools, that one could imagine.

When you found a little exterior building in Rio belonging to what we call the people, you found it covered with primary colors, ornamented in a way which may be childish. It gives the idea of the joy of life, and gives an idea that the people, in this and other things, have taste. I mean literally that they have taste. The taste may be bad taste or good taste, but it is a most agreeable relief from the towns in Canada, where to such a degree the people have no taste at all, either good or bad. (Laughter) I mean literally, by that, that most of us are most indifferent about the buildings that are erected in our city and about the things that we see. We really can take any unction to ourselves that we like, but we really do not care; we have no taste at all. Those people's taste is often bad, but it is taste; they like something. (Laughter and applause)

Their pavements are like the tessellated mosaic pavements you see in the rotundas of hotels. For pavements outside I do not think this is very good taste, but it is very beautiful. They have, at the edge of their sea, a wonderful balustrade of granite or schist---hard rocks at all events-very substantially built, beautiful steps down to the sea, and a colonnade of pillars, and out of the houses in this beautiful section of Rio the people come in their bathing dresses and step down those steps to plunge into the perfect sea and face the tide. They go by thousands, and then go back to the houses in their wet clothes. A large part of the community turns out every day to enjoy that kind of life.

Again, they have those curious conical peaks, one of which is called The National Life, and on one there is an aerial tram. On another, called Hunchback, you can go up a cog railway, and on the top of this extraordinary pinnacle there is a perfectly delightful little tea-house, administered by the City Parks, an indication of how the people live, as they sit around them, and how they enjoy life.

I think their hotels and their shops in Rio are less fine than in Buenos Ayres, and are not nearly up to the same standard, but everything they have in connection with the laying out of the city, the paving of the streets, the administration of the street cars, and the civic life generally, is infinitely superior to what we have in Toronto. Rio is not a point of manufacturing, it is a point of consumption, a market-place--not a place that is likely to develop greatly, because the country is tropical to the north, and not closely enough connected to gas, factories, or that sort of thing, to develop greatly.

We went by rail to Sao Paulo, in the south, and there you go at once through a country so closely cultivated that it is almost divested of forest, and right back through the country they have to burn even the roots that are pulled up. Every scrap of wood is used, even what we would not use in a fire .is used in the wood-burning engines of their railways. They are, however, replanting trees at a rate that makes one ashamed of our own country, where we evidently intend to live until everything is gone before we begin to be wise in that respect.

In this country, which is now sub-tropical, we pass gradually to a colder type of land, a rougher land, a land of cotton, corn, rice and coffee, a cattle-raising country. While you hear only, in countries like that, of their exports and imports, and judge a country like Brazil, you see its ability to raise crops like cotton. I pass on the thought that now the world does not seem to be as large as it used to be, and we forget the things that are going on in connection with their internal trade.

Brazil, like Mexico, is a country where most of the people are dressed in cotton, and until recently Brazil imported cotton very largely for its own purposes. The largest mills are in Brazil and Mexico, but they had to import the cotton in order to make the fabric. They now raise enough cotton for their own requirements, and a little for export. They may raise one kind, and import another kind, but on the whole they have cotton to export, which is quite a great accomplishment. They are becoming more industrial, as they are having so much more coffee or rubber to export. Again, they had to import very largely their rice, because they are a rice-eating people. They brought the Japanese people there, and they had them not only to raise rice in the water, but burned rice, and Brazil now raises rice enough for its own use, and it has no need to import rice. It will undoubtedly reach the point before very long that they will be able to export cattle steadily. They cannot raise cattle as easily as the Argentine, or perhaps as profitably, but they will have to resort to cattle to export, there is no doubt, as the population comes to them and transportation makes it possible.

We went to visit the Dumont Epasinade, an English company owning the largest single block of coffee bushes in the world, but not so large in their entire holdings as Smease Company, a company developed entirely by a poor German boy who, forty years ago, was earning wages in Brazil. The Dumont Epasinade, however, is the largest block anywhere; it is 30,000 acres of land altogether, 15,000 of which are planted in coffee, which means about 5,000,000 coffee bushes. Now, this is an illustration of large land-holding by companies or by individuals, which work with a low class of labor, one with very low standards of comfort, and probably only possible because of that fact. On this estate there are sixteen villages in which about 6,000 employees live, and those employees are Spaniards, Portuguese, Italians, Armenians, Turks, Indians, negroes. They are often to a large degree mere immigrants, who may become migrants, and who may go back as soon as they have money. They are not usually additions to the population.

This plantation, I may just say incidentally, has forty acres of tiling on which to dry the coffee after it has been taken from the bushes. Near it there was a great stock farm, the McNeill Stock Farm, where we had made arrangements to go and see cattle-raising on a large scale in Brazil, but that very day the gentleman came out with his wife because of some illness, and we were not able to see that; but they are raising cattle successfully, and that will gradually grow to be important.

I spoke about Brazil. If you go into its history at all you will find that the back country was thoroughly covered with forests, and rich beyond imagination agriculturally. It has its own railroads, but it has only a wild people there; it is not touched; in a sense it is virgin land that the world has yet to break into, and it will eventually support an enormous population:

The city of Sao Paulo itself was only a comparatively small city thirty or forty years ago, but it now has a population of about 400,000, and as it is 2,500 feet above the sea they are a very vigorous people, and much more capable commercially than people at Rio or other places of Brazil. Indeed, they express the industrial and business ability of Brazil more than any other part. There are many farmers, many British, Scotch, Germans, French--all kinds of people there. Their clubs and everything of that kind express the same love of richly-painted buildings. They are gamblers, as they are everywhere else. I noticed in a club there, as I did in Rio, and afterwards in Buenos Ayres, that while a lot of business men get together at a luncheon in a restaurant, when the bill comes it is one bill, although they have all ordered their luncheons separately, and with it comes the dice box, and the dice are thrown to determine who is to pay the bill. (Laughter) You cannot walk a block anywhere in one of those South American cities without somebody offering to sell you a lottery ticket. Races are the greatest event of the week, and take place every Sunday afternoon. You can realize you are in a gold-rush part of the world, which has not settled down to some of the most serious things, as they will when they come to try to pay their debts to Europe. (Laughter)

You will remember that at Sao Paulo, Hugh Cooper, who was well known as an engineer, made the first visitation to South America, for North American interests, and he cabled one day the amount of power that could be developed from the Parnahyda River, and in that way caused the great investments which the Brazilian Traction Company have now made. I may say that that company is the cause of the improved material condition of the cities of Sao Paulo and Rio, because without their waterpower, without their telephones, their railway and the utilities that they control in those cities, instead of being superior to us in material effort they would be away behind us. In Sao Paulo, a city of 80,000 to 90,000 people, you can travel 2,500 feet in a short distance on the cog railway, built by English capital many years ago, and the magnificent vistas that you see are unique, because you start in mist and cloud always and go down into the sunshine below, beautiful beyond anything that one can imagine.

From Santos we went by the Royal Mail Steamer "Alma Sera," another perfectly superbly appointed boat. One would not wish to travel anywhere in the world under more superb conditions. As you go you may notice, at sea, that the sea-water is slightly different in color, and that it seems to be colored with sediment, but you are really in the LaPlata River without knowing it. It is 130 miles wide at its mouth, and you really sail in it for some hours before you realize that you have left the ocean and are in this river.

The first port in the river is Montevideo, in Uruguay-a modern city, not nearly so important as Buenos Ayres, but with fine banks and fine public streets. Uruguay is a very thinly covered country, entirely settled from Europe in comparatively modern times; a grazing country, not ordinary agriculture, almost all pastoral pursuits, a very prosperous, a very hardy people, a little fond of turning their political differences into fights, but otherwise a stable people, bound to be heard from in an important way as the world grows older.

Montevideo is a city of about 300,000 people, and as I say important, independent, quite determined that they will neither become a part of Brazil nor of the Argentine, although they are much smaller in area.

The night steamer between these places is the most palatial thing afloat I have ever seen in my life, and it has no other purpose than to enable you to sleep over-night while you pass from one place to the other. It is gorgeous, with money spent beyond any reasonable sense of gain, indicating the kind of pride of which I have spoken.

At Buenos Ayres, the river is still thirty-four miles wide, and again you seem to be on the wide sea, only that the water is somewhat discolored. It is only the other day that Buenos Ayres sprang into being a great world city. Before the present port was built a boat with a draught of only fifteen feet had to anchor twelve miles away from the city in the open roadstead, and everything went ashore by lighters. Today the river is kept open by constant dredging, but still a boat with a draught of twenty-five feet picks the mud up in the bottom, and drags, more or less, on it. Still all the surroundings of a great port city are there.

The city has one-fifth of the entire people of the Argentine, the population of which is about 7,000,000 or 8,000,000-not very far, you notice, from that of Canada. It had no possible advantages whatever. Less than many another place on the prairies, with no trees whatever, and the front of the river ugly, it had nothing pleasant to look at. What they have accomplished there, which I have tried to indicate, will probably cost as much as Chicago. While the buildings will not be as permanent in their character, it is far more beautiful than Chicago, and far more wonderful in its accomplishment. They have miles and miles of parks. You may drive in your motor for hours in them, in which there are wonderful artificial lakes. Perfectly wonderful things have been done in tree-planting, the trees being brought in from outside. The trees are of a character that we would plant here or in Manitoba, perhaps a little more southern than that, but in the main not unlike ours.

In statuary, all South America, is just as positive about its desires to have statues to celebrate its events as it is to have fine buildings, and its taste in the statues is a little like the taste in its buildings. The statues axe very funny, very grandiloquent, and are all over the place, and evidently they must express their desires in that form of plastic art. Music they have everywhere. They love music, and produce many of the world's musicians. The opera house in Buenos Ayres is famous as one of the greatest opera houses in the world.

What one notices about Buenos Ayres, I think, is that there is almost no middle class. There are the very rich people, because the owners of those great lands and other interests of that kind live either in that city or in Paris. They do not often live in their own properties. They live as absentees as far as their properties are concerned, and spend their money in a most profuse way. They have Harrod's store there, and a store called Thompson's, which belongs to Harrod's, which are perfect palaces alongside of any stores which I have seen anywhere. Ours are mere warehouses beside them. They sell the most expensive goods, and seem to make a great deal of money when times are good, and they would have pretty hard times when times are poor.

Everything about Buenos Ayres strikes you as a city where the rich are too rich and the poor are too poor; where there is an absence, or almost an absence, of the middle classes. One result of that is, that all labour, being largely unskilled, is transient; it has not come to Buenos Ayres with the idea of staying there, or staying anywhere in particular. Therefore they strike constantly. A strike may be something settled in a few hours, or it may be settled in weeks. The night that we arrived there was a pouring rain, and the men that drove the taxis struck, but by nine o'clock they had it settled, and after all, we went to the hotel in a taxi. , But they struck in the morning; they did not like an American ship that came in there, one of the officers having shot a black man. They insisted on trying the officer in the Argentine, and they were not allowed to do so, and so all the longshoremen at LaPlata, where the landing is, struck, and for two or three weeks refused to unload the ship or have anything to do with it. So they have labour troubles to a very serious degree. I should think that after Brazil it is one of the worst places; but life goes on, and money is spent, and, as far as the most of the people are concerned, they do not mind; they take such things less seriously than we would. Argentina is about one-third the size of Canada, or about three-eighths the size of Brazil. It is, of course, a very variable country. The country drained by the LaPlata and the other rivers, Uruguay and Paraguay Rivers, is very largely a pampas country. Away to the north of that is a mountainous country. Away to the south is the wheat country; away to the south of that again is a country where but one sheep for two or three miles can be raised-so called Patagonia, the wilder country down to the south. Again, somewhere in the southwest there are supposed to be oil fields that may turn out to be of importance, but for all practical purposes at the moment, Argentina is a country which raises cattle, beef, and mutton, and hides and wool for export, and wine for their own use from grapes grown in the Mendoza country, which is settled largely by Italians: In the Andes they put up from two to two and a half million casks of red and white wine, and they drink it all themselves. (Laughter) And very good wine it is, too.

Only a very small part of the country is really developed as yet; and we may as well face the fact that they are likely to be our competitors in the kind of products that they raise. They will probably raise products cheaper than we do because of the low standard of comfort for those who live on the farms, and they will grow those products to tremendous proportions as compared with what they are at the present time.

I have not time to talk to you about Chile and Peru, and they do not interest us at the moment; they are on their beam-ends industrially and financially. Chile has nothing whatever to sell except nitrates and ore, and nobody wants either at the moment. Peru is a sugar country, with some other products, all of which are rather down and out at the moment, and I could not take the time to speak to you about that.

But I should like to make some general statements about South America. The capital for most of the railways and the great developments in South America has come from the source from which all kinds of capital came from before the war-from England. They are administered in great part by British people. The great American houses in South America are British. I mean that England is the country that understands the difference between sending goods to a foreign country and being unable to sell them, and sending them to a great American house that has had experience and knows best the needs and ability of the country. The merchants who are in South America, and will be there after all this trouble is over, are the British-Americans that have been there for a long time.

But it is a fact that most of the manufactured goods going to South America are German. Unfortunately Germany is making goods at the present time. If we can make goods for South America just as we can for China and Japan, we will not establish that trade by the Trade Commissioners, although they are excellent men and are doing all that they can. They will not do it from reading trade records. They will do it by investigating all those countries, both in good and in bad times, and in actually learning what it is that those countries desire to buy; and when that is done we must have transportation facilities on one hand, and we must make goods of the right kind, not only according to sample, but we must make them at the price.

Now, that is a problem not for me to deal with. Every Canadian manufacturer has to deal with it, and he knows how tremendously serious a problem it is; that it is useless for us to talk about some part of the world in which we can dump goods in any condition and at any price. There is no such place, but there is in South America a vast consumptive power, a great deal of money made out of the products which they use and ship, and that producing power can be enjoyed by us just to the extent that we can raise the goods at the price and sell them at the price, stand by the goods, and make ourselves popular in South America, instead of breaking our contracts. In general doing things under motives of conduct that have been in vogue with British traders since Elizabeth's times.

Now, our particular friends to the south within six or eight years have tried to learn foreign banking and foreign trading and international finance--and international politics too. (Laughter) I do not wish to interpose political feelings, but I think, that they have a great deal to learn, and that in South America they made a very bad start. Permit me to refer just to one line of business. I saw literally miles of boxes holding motors exposed to the weather because every covered place had been filled. You were told that they came too late. You were told all kinds of lies by the people at the other end. They were not up to sample, and after all the real fact was that they were sent to South America. because people thought that the way to find out what you can do in South America is to get your agents of the southern firms to tell you how many motors they thought they could sell, and then be wise enough to make more than a certain percent of those. But the next thing they found was that there was no market of any kind.

British and foreign trade is not built that way, and we have to learn that if you can sell goods to substantial people at the other end you are doing a foreign business; but if you are only going to consign your own goods or send them to friendly agents whose ability to pay depends entirely on their ability to sell, then you are not doing foreign business at all. As far as that fundamental difference between the two parts of the world is concerned, I think we should bear that more steadily in mind.

North America was, of course, settled by French voyageurs, couriers du bois, so far as the Canadas were concerned; by great leaders like LaSalle and others, and the great heads of the Roman Catholic Church; by the men that came to New England in the Mayflower; by the gentlemen who settled in Virginia; and by all those that have come from that type of people and with that desire of settlement, that desire of working with their own hands, to found themselves an empire beyond the sea.

Now, South America was settled by the men who, following Henry of Portugal, were engaged in silver and in gold hunting, who sought to find lands that they could despoil, and take away the results of despoiling them. There came first to America, the Spaniards and the Portuguese. They gradually kept murdering, and lessened the numbers of the Indians in every way by cruelty; and then, by very false statements to the Pope and to the King of Spain and the King of Portugal, began the introduction of black men, and through slave labour attempted to develop that country.

That is the difference in the settlement of the two countries. There no man dreams of small landowning, but great families, the fathers of important people, own large areas of land. And that land can only be worked by agricultural workers with a low standard of comfort, like the people from southern Italy, or by a hardier and abler people who will make for themselves a place in the land like the people from northern Italy. There is that difference between the two parts of the world which, if it does not last forever, and I do not think it can, will yet last for a very long time to come, and will make the nature of the two parts of the world quite different.

Our business, I think, is not to try and alter them or to give them advice. Nobody likes advice. Our business is to understand them, and our business, beyond anything, is to understand what they mean when they say sympathetic--to have sympathy with them, to really understand them, understand them in a kindly way. They are going to have their own tremendous influence on the development of the world, and they are going to have their intense pride in their own country and their people and their own kind of civilization, and that we want to respect.

They have manners, they are Latins, inversely to their conduct; and we are supposed to have conduct inversely to our manners. (Laughter) You will excuse me if I say that we often go to those countries, and there are faults on both sides; we have conduct that often does not involve manners, and conduct that is not particularly admirable. We are often offensive; and may I say that nothing is so offensive to all South America as the arrogance of our friends to the south in calling themselves "Americans." If any citizen of the United States could understand the sort of introduction he makes for himself anywhere in South America. by saying that he is an "American" he would never be caught in that act of folly again, and he would try to find a name for his country other than the one he uses.

Now, I just want to say, finally, that if we are right sure of our ground in what we are doing, we can afford to be disliked. England has always followed that policy. "If you are sure of your ground you can afford to be disliked." But you cannot afford to be hated if from time to time you do the things which cause the people, who feel that they are in every respect your equal, to hate you. (Loud applause, the audience rising and giving three cheers)