History of the Great Lakes and the Chicago Drainage Canal

- Publication

- The Empire Club of Canada Addresses (Toronto, Canada), 29 Nov 1923, p. 343-351

- Speaker

- Coleman, A.P., Speaker

- Media Type

- Text

- Item Type

- Speeches

- Description

- The mill-ponds which form reservoirs that provide a constant and steady flow of water in Ontario. Nothing in the world to compare with our Great Lakes. The Great Lake system as the most artificial thing of the kind I the world, and also a very temporary system. Ways in which that is so. The origins of the Great Lakes; how they were formed. The question of the Chicago Drainage Canal. Concern over the low level of the lakes. The changing nature of the water level. The feasible engineering feat of draining the upper lakes into the Mississippi. Consequences of such action. The speaker’s suggestion that we ought to have a combination of everybody interested, the people on the banks of the Mississippi and all the States that touch on the Great Lakes, and all the States whose grain comes out by the Great Lakes, should combine and have the removal of water that is now taken done away with completely, an let the sewage of Chicago be treated in some other way.

- Date of Original

- 29 Nov 1923

- Subject(s)

- Language of Item

- English

- Geographic Coverage

-

-

Ontario, Canada

Latitude: 43.70011 Longitude: -79.4163

-

- Copyright Statement

- The speeches are free of charge but please note that the Empire Club of Canada retains copyright. Neither the speeches themselves nor any part of their content may be used for any purpose other than personal interest or research without the explicit permission of the Empire Club of Canada.

Views and Opinions Expressed Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the speakers or panelists are those of the speakers or panelists and do not necessarily reflect or represent the official views and opinions, policy or position held by The Empire Club of Canada. - Contact

- Empire Club of CanadaEmail:info@empireclub.org

Website:

Agency street/mail address:Fairmont Royal York Hotel

100 Front Street West, Floor H

Toronto, ON, M5J 1E3

- Full Text

HISTORY OF THE GREAT LAKES AND THE CHICAGO DRAINAGE CANAL

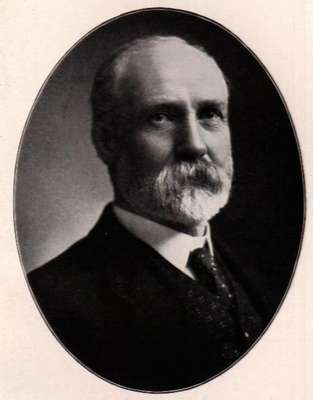

AN ADDRESS BY A. P. COLEMAN, M.A., PH.D.,

F.R.S., LL.D., PROFESSOR EMERITUS OF GEOLOGY,

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

Before the Empire Club of Canada, Toronto,

November 29, 1923PRESIDENT WILKINSON introduced the speaker as one who would deal in a practical way with a subject of very considerable interest to every member of the Club. PROF. COLEMAN was received with loud applause.

PROFESSOR COLEMAN Mr. President and Gentlemen,--The Hydro in Ontario gets a large amount of publicity, but there are some features of the Hydro that I have not seen referred to in the newspapers, and perhaps I might begin by saying that the Hydro has the finest millponds in the world. There is no other set of reservoirs providing water for any purpose to compare with that of our Great Lakes. For instance, the Mississippi River at certain seasons has very low water, while at other seasons, when the snow is melting upstream, the water is from thirty to fifty feet higher than before. All other great rivers have considerable changes in their levels. The Niagara River and the St. Lawrence, whose water is the

--------------------------------------------------

Professor Coleman is a graduate in Arts of Victoria University (Prince of Wales gold medal), and Ph.D. of the University of Breslau; F.R.S.C. and F.R.S.; awarded the Murchison Medal for distinguished geological investigation; professor of geology in the University of Toronto for more than a quarter of a century. As a practical geologist he has done field work in every continent of the globe.

--------------------------------------------------

same, are very constant and steady in their level; that is one of their striking features. It can be said that there is no great river in the world where there is such constancy of level as in our rivers, and that is because of those mill-ponds, which form reservoirs that provide a constant and steady flow of water.

As loyal Canadians we are very proud of the Great Lakes, and we think they are exactly where they ought to be. (Laughter) But are they? Why should there be any Great Lakes as a boundary between Canada and the United States? Why do not other countries have great lakes, a string of them tied together by rivers, but which finally plunge over the Fall at Niagara and over the series of rapids in the St. Lawrence? It is an extraordinary arrangement, and there is nothing in the world to compare with it.

Our Great Lake system is the most artificial thing of the kind in the world, and what is more, it is a very temporary system. By that I mean that the whole affair began about 25,000 years ago; and if man had not taken a hand in the matter it would probably end in 25,000 years more. We have great lakes because of an event that occurred perhaps half a million years ago-the ice age. Before the ice age there was only a great river, and so far as we know there were no lakes in the present region. This river flowed down from Lake Superior basin through that of Lake Huron and came out-of all places in the world-at Toronto, which seems to have been a sort of meeting place even before the ice age.

You naturally ask how one can know anything about an event that happened 25,000 years ago. The reason is that all the towns from here to Barrie got their water supply from the old channel dug deep down in the rocks underlying the present surface. Their water supply comes from the ancient river valley I have spoken of. How did that Great River come to be abolished so that the lakes could take its place? It is accounted for in a very interesting way. Nearly all our rivers run either north or north-east. Did that ever occur to you? Now, the ice that covered this country 25,000 years ago came from the north-east, and the effect was to dam the rivers up; and this Great River I referred to, the predecessor of the St. Lawrence, was dammed in the East.

Of course this damming of the rivers by ice was a purely temporary thing, and lasted only a few hundred thousand years. It was not a matter of very vital consequence, but the ice from the north brought such a mass of materials with it in its downward motion that it filled up the great river and more or less blocked the whole drainage of the Eastern part of Canada and the adjoining United States.

Certain very interesting phenomena took place towards the close of the ice age. The great lakes were filled with masses of ice when the glacier reached its greatest extent, but when the ice slowly thawed away from the south, the lakes were set free gradually--not all at once--and there were ice dams that held up the water for a long time.

The first really great lake began to flow out at Chicago. Please keep that in mind, for I am going to return to that later. Although the lake at first flowed past Chicago, as the ice retreated farther it found an outlet by what is now the Trent Valley Canal into the Bay of Quinte, so that the canal had its prototype in a great river. The next time you go to Montreal travel by day, and you will see that an insignificant river wriggles along at the bottom of a broad valley. It is an entire misfit, for the reason that it has inherited its valley from the river that corresponded to the Niagara at that time. Now, you may wonder why the water of the upper lakes does not still flow out by the Trent; and why we should have the present round about arrangement. Why doesn't it take a straight route down?

Here comes the extraordinary feature of the affair. We find the shores of those old lakes perfectly preserved in many parts of Ontario, but tilted up towards the north-east. The crust of the earth was loaded with the ice, and sank under the load, and when the ice thawed it rose again. As the land was lightened of its load of ice at the end of the ice age that channel was destroyed. The elevation was so great that the water could no longer flow out in that direction.

When the ice thawed back still farther, the Ottawa region was set free. The Ottawa people want a canal there now to take the traffic of the upper lakes down to Ottawa and Montreal. The water did at one time flow down the Ottawa past Montreal.

For the water to flow that way would seem a very suitable arrangement for a person who lived in Montreal. However, the rise of the Continent that came with melting of the ice was still going on as the load was decreased; the region was rising still towards the north-east, and reached to a point where part of the water went out by the Ottawa, part went around by the St. Clair channel, and probably a little of it went out at Chicago. It is just possible that the Nipissing Great Lake, as it has been called, because its outlet was up in the Nipissing region--had for a short time three outlets. Just think what a delicate balance of forces. One great lake as large as all our upper lakes put together, covering 90,000 to 100,000 square miles, and with certainly two outlets, possibly three. Well, that was a very interesting state of affairs, you can see. It was a very moot question as to which outlet should have the advantage and become the final drainage system for the upper lakes. You can see that it was a matter of great delicacy.

Now, suppose that the elevation of the land towards the north-east had stopped there. Then we should have had a very neat arrangement, should we not? The Montreal people would have been happy, because part of the water would have flowed out past them and there would have been a chance to make a canal up there. The Chicago people would have been happy because some of the water would have gone the other way; and the Toronto and Hamilton people, and all the people on Lake Erie would have been happy because some of the water came their way. A very neat arrangement. But it was too delicate a thing to last; it was too close a balance of things to be permanent. The rise in the land continued, and the water was backed up, and finally the whole of it began to flow in the Niagara Channel.

You have all been to Niagara Falls frequently, I suppose. I make a pilgrimage there twice a year, sometimes oftener. There is a very fine gorge below the Falls, is there not? I think the Gorge is even more interesting, with its rapids, than the Falls themselves, although the Falls are among the most magnificent in the world. That gorge is six and a half miles long. Why are the Falls not at Queenston? They are not at Queenston for the very good reason that they have cut their way back, and they are still cutting at the rate of 4.2 feet per annum, until they are at the particular point we are familiar with. Why are they there? Why are they not farther north or farther south? You can see that there is a whole series of problems, a very tangled set of problems, that come in there. If the Falls had their own way, and the Hydro never took any part in the matter, they would ultimately cut their way back to Lake Erie, and there would no longer be the Falls, but there would be a rapids, and Lake Erie would be drained, and the boundary between Canada and the United States would be a river and not a lake. Lake Erie is a very shallow lake; it would not take much to drain it.

Whether that would be an event to be desired or not I do not intend to discuss at present. It did not take place. The Falls only moved back 61/2 miles out of the total distance that was possible. That is perhaps sufficient in regard to the Falls.

We want to come to the last point, that is, the question of the Chicago Drainage Canal. We are worried about water. We have the biggest supply of fresh water in the world, but we are worried because the lake levels are low, and we are looking around for reasons why lake levels are low. If you have seen the chart of the lakes prepared by the Hydrographic Survey you will find that they go up and down like saw-teeth; a record has been kept for a long time of the levels of the lakes, and they are always going up and down; there is a range of five or six feet between low water and high water, seldom more than that. We are now at the bottom between two of the saw-teeth; and the question arises whether the water is lower than it has been before. I think it has been about as low in previous years. But suppose that the low water is drained off four or five inches more, that means that every harbour that is approaching the limit for vessels that enter it is going to be hampered to that extent. That is what is happening now. As one might say, we are at the peak of the depression, and a few inches only added to that peak will set the whole thing wrong.

I was along the Welland Canal a month or two ago, and the vessels were coming down with their loads of grain at that time, and some of them were getting aground. Now, if the water sank a foot the average vessel that brings grain from the upper lakes would be stuck in the canal. There is no doubt they have had a lot of trouble this year, more than for many years before, and that trouble always comes at the worst time. The lakes are lowest at the end of summer, and then is when you want the best flow of water in order that the vessels shall carry their loads right down through and reach Montreal where the cargo can be put on board the ocean vessels.

That brings us to the question of the Chicago Drainage Canal. The next time you go to Chicago, have a look at the south-eastern side of the city. One of the railway lines swings away around and comes in by the rear. You can see that there is a depression, very like the depression I referred to in the Trent Valley-a broad depression. Now, you know that when Chicago started it was on Chicago Creek, a muddy, sluggish little stream that flowed into Lake Michigan. Chicagoans did not like the creek because it got very turbid with sewage, and spoiled their water supply, which they got out of the lake. They decided it would be a neat thing to put affairs into the old postglacial position. There is a very famous geologist at the University of Chicago who has given an account of the old outlet at Chicago-Prof. Chamberlain. I don't know whether he has been consulted in the matter, but they presently found that instead of letting that dirty little creek flow into Lake Michigan, they could dig a ditch a little way further south-west and the water would flow into the Desplaines River, which flows into the Illinois River, which in turn flows into the Mississippi River. Now you see the connection of affairs. The ancient lakes did flow in that dire tion at one time; all Chicago had to do was to deepen the old channel a little and turn the water in that way.

There was one point I should have mentioned. I said the land had stopped rising; if it had risen 50 feet more the whole of the water of the upper lakes would have drained into the Mississippi. It would not be a difficult thing for engineers of the capacity of Chicago Engineers to deepen the drainage canal and turn the whole water once more towards the Mississippi. That is an entire possibility. It is a quite feasible engineering exploit.

It seems to me that we ought to pay rather particular attention to this matter, because if the upper lakes were drained into the Mississippi we should have at Niagara only the drainage of the Lage Erie Basin, and that has been estimated at about 15 percent of the total volume that goes over Niagara. Niagara would be reduced to a river something like the Ottawa. What that would mean from the scenic point of view, of development of power, and what it would mean for navigation, is something that of course you can all appreciate; it is not necessary to labour the point.

You can see that we are before a very important proposition-the question of the drainage of the water to the Mississippi instead of to the St. Lawrence. It is entirely possible to drain the whole of the upper lakes in that direction, and in that way of course to change the whole future course of events here.

Now, Chicagoans are planning, and I think they have already got specifications for a ship canal that is to go down to New Orleans. They have that in view. At first it will be a shallow canal, but there will be a demand to make it deeper, just as our Welland Canal has been deepened twice; the same sort of thing is going to operate there.

I always wonder why St. Louis did not make a disturbance over the sewage that Chicago was sending south-west into the big river. However, the Louisians, I suppose, think that it would be sufficiently diluted on the way down to be potable when it reaches that stage. There are a lot of cities on the Mississippi, and if you have ever seen Chicago sewage, you would think it was a very hurtful thing to mix with your water supply.

Now it seems to me we ought to have a combination of everybody interested--the people on the banks of the Mississippi and all the States that touch on the Great Lakes, and all the States whose grain comes out by the Great Lakes, should combine (applause) and have the removal of water that is now taken done away with completely, and let the sewage of Chicago be treated in some other way. (Loud applause)

MR. R. S. GOURLAY expressed the thanks of the Club to Professor Coleman for his very timely and interesting address.