The Finance of the War

- Publication

- The Empire Club of Canada Addresses (Toronto, Canada), 25 Apr 1918, p. 216-225

- Speaker

- Walker, Sir Edmund, Speaker

- Media Type

- Text

- Item Type

- Speeches

- Description

- Now at the gravest moment in the history of civilization. What we are fighting for. Trade balances in 1913 when our fiscal year ended on the 31st of March compared with figures from last year. The importance of trade figures with the United States. Our immediate problem to manufacture and produce every kind of article needed by Great Britain and our Allies from wheat to aeroplane engines. Paying our part in the War. The realized need for Canada to extend credit to Great Britain, at least for a part of the munitions produced by us, and later, to extend that credit past the war. How Canada could meet this need and how the imbalance with the United States factors in. Inducing the American mind to appreciate that every farm and every workshop in all North American is necessary for the support of our armies. An explanation of how we settled our account when we had securities to sell last year, with figures. The situation in the present year. The need to prevent the bringing into this county unnecessary goods and also to prevent within Canada unnecessary expenditures, even if the goods are made here, and why this must be done. Impressing upon people that whatever they receive over and above what will provide for their necessaries does not belong to them as absolutely as in peace times but should be turned back immediately into War Loan Securities. The difficulty experienced in England of making the public understand the purpose and value of the War Certificate. The lack of signs of war in Canada that are to be seen already in the U.S., and to what this is due. Economy as a sort of fine art. The rebuilding of railroads all over the world, particularly in North America as one of the first things to be done after the war. Renewed activity in every direction which will probably be accompanied by a long period of high prices. Developing Canada's water power. A brief review of the Western world's natural resources. Canada's advantages in terms of natural resources. Paying our debts after the war is over. Canada, coming into its own during and after the war. Our men, coming back with a vision of hope and courage, and a resourcefulness and leadership such as Canada has never known before.

- Date of Original

- 25 Apr 1918

- Subject(s)

- Language of Item

- English

- Geographic Coverage

-

-

Ontario, Canada

Latitude: 43.70011 Longitude: -79.4163

-

- Copyright Statement

- The speeches are free of charge but please note that the Empire Club of Canada retains copyright. Neither the speeches themselves nor any part of their content may be used for any purpose other than personal interest or research without the explicit permission of the Empire Club of Canada.

Views and Opinions Expressed Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the speakers or panelists are those of the speakers or panelists and do not necessarily reflect or represent the official views and opinions, policy or position held by The Empire Club of Canada. - Contact

- Empire Club of CanadaEmail:info@empireclub.org

Website:

Agency street/mail address:Fairmont Royal York Hotel

100 Front Street West, Floor H

Toronto, ON, M5J 1E3

- Full Text

- THE FINANCE OF THE WAR

AN ADDRESS BY SIR EDMUND WALKER

Before the Empire Club of Canada, Toronto,

April 25, 1918MR. CHAIRMAN AND GENTLEMEN,--We are at the gravest moment in the history of civilization. That is a statement which, unfortunately, needs no further explanation. We are all aware that it is the gravest moment not only its our history but in the history of the world. We are a little like a man trying to cross an unsafe bridge who, if he takes his eyes off the bridge for a moment, may be lost. And yet, as he crosses he will, from time to time, glance at the farther end and endeavor to anticipate what he will find on his arrival there.

There are in Canada and elsewhere a great many people who comfort themselves with the idea that Right always wins in the long run, but I am afraid history does not justify that kind of optimism, if by "the long run" we mean time measured merely by centuries. A Christian Emperor of Rome was successful over a pagan Emperor and a great step in the right direction was gained; but we know that Rome, later on, was visited by the Goths, and that other Huns with another Attila over them swept across Europe. We know, too, that the Asiatic Tartar drove himself between the European Slavs and is still there in Hungary and we have not yet got

----------------------------------------------------------

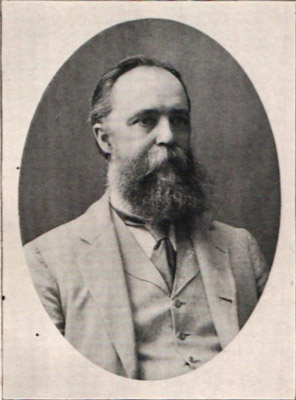

Sir Edmund Walker is well known as a leader in Canadian Banking and Financial circles generally. Moreover, Sir Edmund has been equally prominent in Patriotic and Educational work, so that with a thorough knowledge of finance, he combines that broad outlook for the present and future citizenship of Canada which led him to discuss his subject from a human as well as economic point of view.

----------------------------------------------------------

the unspeakable Turk out of Europe. It is therefore evident that we have no reason for comforting ourselves with the idea that we shall win this war simply because we are right.

There is, however, one great difference between the allies in this war and those who happened to be right but who-were defeated in these earlier wars. We are fighting now for the kind of individual liberty that began with the. Anglo Saxon in King Alfred's time, and for the right of small nations to develop without menace from the large. We are not fighting to save dynasties or emperors or kings,-and we are going to win this war because the Tommies in the trenches (in spite of all the fun that Bairnsfather can make out of them) know why they are fighting, know that it is for the liberty of the world, without which life is not worth living. As has often been said, if we lose it will not be due to those who are fighting our battles in the trenches, in the air or on the sea, but to the people at home having lost their nerve, having become warweary and failing to back up the men who are fighting for them at the front. Yesterday I saw a message which a gentleman had received telling of the wonderful optimism of the troops during the critical period of the last few weeks, and it indicated that cheerful optimism is greatest at the front, and diminishes in proportion as one goes back therefrom.

In 1913 when our fiscal year ended, on the 31st of March, we were in the extraordinary position of a country with what we then thought an enormous foreign trade amounting to $1,063,000,000, but with a balance against us of $310,000,000 and with interest upon our, foreign indebtedness amounting to $125,000;000 or $150; 000,000, and we looked to England to purchase enough securities from us to square that account, as she had done for several years before, and she did so.

Last year our foreign trade had grown to $2,043,000,000, and we had so completely turned the balance that our exports were $315,000,000 more than our imports, and it is clear that if those exports had been to customers who could pay as ordinary merchants do, our finances would have been very easy and we should have paid our interest on our foreign debts without difficulty. But I would like to draw your attention to the fact that in that year we bought from the outside world $865,000,000 worth of goods of which $678,000,00 worth came from the United States, and that figure represents approximately $440,00,00 more than the value of the merchandise which the United States bought from us. I ask you to carry that figure in your mind because it is tremendously important.

For the fiscal year ending 31st March, 1918, our foreign trade was $2,564,000,000. That is to say, our foreign trade in 1918 was two and a half times as great as it was in 1914 when the War broke out.

Our immediate problem is to manufacture and produce every kind of article needed by Great Britain and our Allies from wheat, to aeroplane engines, indeed, everything from the simplest article of food to the most complicated kind of manufactures. In the early part of the war we did not dream that we could pay the cost of our share in it, and we asked England to help us at the rate of so much per month, an arrangement which lasted for four or five months when it was realized that we had to help ourselves. Then we realized that it was Canada who should extend credit to Great Britain, at least for a part of the munitions produced by us, and later, when England had poured into the United States through the Canadian mint over $1,00,00,000 of gold sent here from her overseas Dominions, we all realized that the time had come when she must have credit for a period longer than the war for everything she bought.

Canada, however, could not possibly give long credit for everything she made for Great Britain unless she were a self-contained country, and unless. the interest on her foreign indebtedness were met in some other way than payment in international money. If we could feed and clothe ourselves and provide the necessary houses and shops and factories in which to work, and if we possessed all the raw materials necessary, then we could give Great Britain long credit for practically everything. It is evident, however, that if we had to buy from the United States $400,000,000 worth of merchandise more than we sold her, we could not do so. That was the problem we had to face last year and in a still larger degree, it is the problem this year. When the argument was used that we were buying these materials from the United States mainly in order to produce munitions, the natural trading instinct of the American prompted him to ask: "Why don't we make the munitions?" and it was the business of the British representatives in Washington to induce the American mind to appreciate certain fundamental facts in connection with the war, one being that every farm and every workshop in all North America, except Mexico, is necessary for the support of our armies.

Let me for a moment explain to you how we settled our account when we had securities to sell last year. I said at the outset that before the war we always settled by selling securities in Great Britain or to European countries who followed the lead of Great Britain. One of the biggest problems we had to face when war broke out was whether the United States would take the place of Great Britain and buy our securities. They did so in an admirable spirit. Presently it was discovered that we were manufacturing on an enormous scale for Great Britain and we realized that we had the power to absorb large masses of securities ourselves whether for our own share in the war or for that of Great Britain. In 1917 Great Britain took $5,000,000, (a renewal) the United States $187,000,000 and Canada $580,000,000 out of the total of $772,000,000 of Canadian issues offered for sale, and in addition, the banks lent a very large sum on Treasury obligations of the British Government and of Canada.

But when we come to the present year, the United States has closed the market to the world for securities, and Canada is left in the position of absorbing herself, any securities which the Finance Minister may permit to be issued, whether public or private. We shall therefore have to estimate without the $187,000,000 which the United States provided in the previous year by buying our securities. I hope that these figures are enough to indicate what a banker means when he says that everything should be done to prevent the bringing into this country of unnecessary goods and also to prevent within this country unnecessary expenditures, even if the goods are made here, for with every dollar diverted from its present use, a dollar's worth of war supplies can be made which without that dollar will never be made, and every dollar expended on something unnecessary to carry on the war is a dollar's worth of power lost to our cause. That is a precise and accurate statement from which it is impossible for anyone to escape who understands financial problems. We bankers, too, have from the commencement of the war, constantly urged the necessity for thrift, partly, of course, for the sake of the saver, but infinitely more for the sake of the country. I suppose some people thought we were anxious to secure deposits, while others thought we were speaking of thrift in the abstract because thrift is good for the individual. But it became quite apparent quite early in the war that it was necessary to practise thrift because the individual might very well spend money that should be used in the buying of securities to help win the war, and therefore thrift for the country as a whole is the vital thing. The men and women working in the munition shops receive at the end of the week certain pieces of paper called bank notes which they regard as money and which has the purchasing power of money. That money is created really in consequence of the munitions being made. It is the making of the munitions that creates that money or that instrument of credit, and it is not helpful if the person getting that money as the price for making the munitions shall buy with it more than the reasonable necessaries of life. We have no right at such a time as the present to spend our earnings as we please. After keeping ourselves in food and clothes and shelter as economically as possible, it is our duty to hand the remainder over for War Bonds. From the first I have advocated that we should issue securities so small that on pay day every working man or woman would have the opportunity of purchasing a bond, at least as low as ten dollars. We should, however, at the present time issue a Thrift stamp and a War Savings stamp, and it should be made possible for everybody to invest as little as twenty-five cents, or even five cents, in the furtherance of our fight for democracy. It should be impressed upon the minds of the whole people that whatever they receive over and above what will provide for their necessaries and keep them decently, does not belong to them as absolutely as in peace times but should be turned back immediately into War Loan Securities.

In England it was a long time before they could make the public understand the purpose and value of the War Certificate, and in spite of much advertizing they were not quite as successful as some people thought they should have been. today, however, they are selling weekly to the working men and women of England an average of 12,000,000, Sterling of these apparently trifling War Certificates, while as yet in Canada nothing of that kind has been done; the smaller sums have so far been ignored.

We in Canada are far less observant of the conditions with respect to the war than are the peoples of the United States. I have not seen a piece of white bread in the United States for months. In Canada one does not see the signs of the war that are to be seen already in the United States. This is partly due to the fact that the heads of the house are afraid of the other end of the house. The most dangerous part of the house is the kitchen, and people in the kitchen are apt to think that economy is another name for stinginess. We all know, that the Canadian farmer who is as close as can be if you are trying to sell him a cow, will, if you are his guest, load his table to profusion. Now, if there is one thing more clear than another it is the fact that economy is what marks the difference between an educated man and a savage. Economy indeed is a sort of fine art. The most marked characteristic of a savage is wastefulness and we should be ashamed of ourselves if we take no pleasure in economy for its own sake. The other day my attention was drawn to a very clever thing in one of Chesterton's books which I jotted down. He says "If a man could undertake to make use of all the things in his dustbin he would be a broader genius than Shakespeare."

After the war is over we shall have an accumulation of capital such as the world has never known before. We shall have courage in the owners of manufacturing establishments unknown before, and we shall have in the entrepreneur an experience, skill and scientific ability unknown before, and we shall be called on to face the competition of the other nations who will be in the same condition. When we think about Germany and her cleverness in the past and of her renewed energies after the war, there may be some comfort in considering what advantages Canada and the Empire have. If we are going to have a peace so established that it will be a guarantee for the future, well and good, but we know perfectly well that we may not secure that kind of peace. We may have a kind of peace that will cause the English-speaking peoples throughout the world to lock themselves together along with the French and certain other nations for mutual protection and development, and these nations may have to enforce justice and peace both for themselves and the rest of the world.

One of the first things to be done after the war, will be the rebuilding of railroads all over the world and particularly in North America, because it has been impossible with the freight rates of recent years followed by war conditions to keep the railroad beds and rolling stock in proper condition. Then there will be the carrying on of all the building that has remained undone during the war and the opening up of all sorts of new enterprises and of virgin resources. We shall see renewed activity in every direction which will probably be accompanied by a long period of high prices-I am not talking about the period of reconstruction-I will not try to guess how long that will take or what it will involve. We shall have the greatest water power of any country in the world and when our resources in this respect are fully developed around the Great Lakes and elsewhere and always leaving out of account that vast and little developed Siberia, which would be a formidable competitor of ours were it under a progressive democracy.

We have in Canada almost as much coal as there is in the United States.

England controls at least 60% of all the gold in the world.

If we are faithful to our duty in replanting, we shall still remain one of the great timber and pulpwood countries of the world.

With regard to steel and copper, England-and Canada are better off than Germany, and with the United States linked up with us no combination in the world could be as strong.

Canada possesses 85 % of the world's nickel, and what France does not control of the other 15% in New Caledonia, Great Britain owns in Norway.

The major part of the zinc concentrates necessary for the making of spelter is mined in Australia, and these mines, before the war, were owned by a wonderful combination of German metal companies through direct ownership or under long contracts, and 80% of all the zinc concentrates went directly to Germany while Britain got 3%. Before the war Germany produced 280,000 tons of spelter, Belgium under German control 200,000 tons, the United States 300,000 tons and Great Britain 60,000 tons. Great Britain used 200,000 tons, of which she got two-thirds from Germany who had manufactured it out of the zinc concentrates she got from Australia. The war ended these contracts and it is unlikely that they will ever be renewed.

Half of the world's tin supply is in Cornwall and the Malay States, and Great Britain controls that and practically the main part of Bolivia's output.

The United States and Canada make now more than half the aluminium of the world, and Germany will not be able to manufacture it because she has not the necessary bauxite clay. Germany was the largest customer of the French supply which constituted about a quarter of the world's total supply.

Before the war the manufacturer of this country consisted largely of articles such as agricultural and other implements and certain textiles needed in the country, electrical machinery, and several classes of articles, depending on basic products such as lumber and steel; we could not be said to be a highly developed manufacturing country. But while the war has been going on, natural developments have been going on, too, and there has been built up at Niagara Falls, New York, and Niagara Falls, Canada, the greatest centre of chemical manufacturing in the world. Also there is being built, on the Detroit River, at Amherstburg, where the exact kind of limestone and salt required is to be found, immense works for the manufacture of Caustic Soda and Soda Ash. When you bear in mind the area of Canada you cannot but feel that almost everything for the use of industrial chemistry exists here, and if our transportation and population and our advancement in science and manufacturing are assured we have the necessary foundation for prosperity. And back of all that, we have something incomparably greater in the largest unplowed area of land in the world where democracy rules, and where there is a decent climate and a decent people.

After the war we shall have a reputation, so far as our people are concerned, second to none in the world, either at the present time or in the past history of the world. English people used to say that Canadians were half Americans, and the Americans would say that we were half English. They did not even recognize the physical type; they know that quite well now. (Applause.)

I have often said that when the war is over and we face the enormous debt, which debt after all mainly represents the savings of the people in making munitions during this war, the war will be paid for-the main question will be the settlement of the respective accounts. No country was ever ruined that owned its own bonds, and we can pay whatever debts we have incurred to ourselves. We shall have seven million or eight million people in this vast country with all its wonderful and still undeveloped resources, and when the war is over we shall have the benefit of the energy and moral courage which has been shown and proved in this war-I am not ashamed to say that I was not at all sure that the Canadians would distinguish themselves as they have; I had no confidence of that kind. I thought of course that they would give a good account of themselves, but I did not feel sure that they would prove, as they have, that they were as good as the best soldiers in the world. All the energy which from 1865 to 1890 in the United States built the railways and filled the shops and the pulpits and every other field of activity, will be duplicated here, but we must not forget that the United States created an army of tramps out of the same war, and also created the Grand Army of the Republic, a very dangerous political institution, and we have to look out that we do not create either of these here. (Hear, hear.) Most of our men will come back with a vision of hope and courage, and a resourcefulness and leadership such as Canada has never known before. (Applause.)